Mandatory Palestine (Arabic: فلسطين Filasṭīn; Hebrew: פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א"י) Pālēśtīnā (EY), where "EY" indicates "Eretz Yisrael", Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity under British administration, carved out of Ottoman Southern Syria after World War I. British civil administration in Palestine operated from 1920 until 1948. During its existence the territory was known simply as Palestine, but, in later years, a variety of other names and descriptors have been used, including Mandatory or Mandate Palestine, the British Mandate of Palestine and British Palestine.

During the First World War (1914–18), an Arab uprising and the British Empire's Egyptian Expeditionary Force under General Edmund Allenby drove the Turks out of the Levant during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign. The United Kingdom had agreed in the McMahon–Hussein Correspondence that it would honour Arab independence if they revolted against the Ottomans, but the two sides had different interpretations of this agreement, and in the end the UK and France divided up the area under the Sykes–Picot Agreement—an act of betrayal in the eyes of the Arabs. Further confusing the issue was the Balfour Declaration of 1917, promising British support for a Jewish "national home" in Palestine. At the war's end the British and French set up a joint "Occupied Enemy Territory Administration" in what had been Ottoman Syria. The British achieved legitimacy for their continued control by obtaining a mandate from the League of Nations in June 1922. The formal objective of the League of Nations Mandate system was to administer parts of the defunct Ottoman Empire, which had been in control of the Middle East since the 16th century, "until such time as they are able to stand alone." The civil Mandate administration was formalized with the League of Nations' consent in 1923 under the British Mandate for Palestine, which covered two administrative areas. The land west of the Jordan River, known as Palestine, was under direct British administration until 1948. The land east of the Jordan, a semi-autonomous region known as Transjordan, under the rule of the Hashemite family from the Hijaz, gained independence in 1946.

The divergent tendencies regarding the nature and purpose of the mandate are visible already in the discussions concerning the name for this new entity. According to the Minutes of the Ninth Session of the League of Nations' Permanent Mandate Commission:

Colonel Symes explained that the country was described as "Palestine" by Europeans and as "Falestin" by the Arabs. The Hebrew name for the country was the designation "Land of Israel", and the Government, to meet Jewish wishes, had agreed that the word "Palestine" in Hebrew characters should be followed in all official documents by the initials which stood for that designation. As a set-off to this, certain of the Arab politicians suggested that the country should be called "Southern Syria" in order to emphasise its close relation with another Arab State.

During the British Mandate period the area experienced the ascent of two major nationalist movements, one among the Jews and the other among the Arabs. The competing national interests of the Arab and Jewish populations of Palestine against each other and against the governing British authorities matured into the Arab Revolt of 1936–1939 and the Jewish insurgency in Palestine before culminating in the Civil War of 1947–1948. The aftermath of the Civil War and the consequent 1948 Arab–Israeli War led to the establishment of the 1949 cease-fire agreement, with partition of the former Mandatory Palestine between the newborn state of Israel with a Jewish majority, the West Bank annexed by the Jordanian Kingdom and the Arab All-Palestine Government in the Gaza Strip under the military occupation of Egypt.

BRITISH MANDATE AND TRANSJORDAN (NOW JORDAN)

Palestine is the name (first referred to by the Ancient Greeks) of an area in the Middle East situated between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. Palestine was absorbed into the Ottoman Empire in 1517 and remained under the rule of the Turks until World War One. Towards the end of this war, the Turks were defeated by the British forces led by General Allenby.

In the peace talks that followed the end of the war, parts of the Ottoman Empire were handed over to the French to control and parts were handed over to the British – including Palestine. Britain governed this area under a League of Nations mandate from 1920 to 1948. To the Arab population who lived there, it was their homeland and had been promised to them by the Allies for help in defeating the Turks by the McMahon Agreement – though the British claimed the agreement gave no such promise.

The same area of land had also been promised to the Jews (as they had interpreted it) in the Balfour Declaration and after 1920, many Jews migrated to the area and lived with the far more numerous Arabs there. At this time, the area was ruled by the British and both Arabs and Jews appeared to live together in some form of harmony in the sense that both tolerated then existence of the other. There were problems in 1921 but between that year and 1928/29, the situation stabilised.

(Editors Note: From Wikipedia The Emirate of Transjordan (Arabic: إمارة شرق الأردن Imārat Sharq al-Urdun), also hyphenated as Trans-Jordan and previously known as Transjordania or Trans-Jordania, was a British protectorate established in April 1921. There were many urban settlements beyond the Jordan River, one in Al-Salt city and at that time the largest urban settlement east of the Jordan River. There was also a small Circassian community in Amman.

Transjordan had been a no man's land following the July 1920 Battle of Maysalun, and the British in neighbouring Mandatory Palestine chose to avoid "any definite connection between it and Palestine" until a March 1921 conference at which it was agreed that Abdullah bin Hussein would administer the territory under the auspices of the British Mandate for Palestine with a fully autonomous governing system.

The Hashemite dynasty ruled the protectorate, as well as the neighbouring Mandatory Iraq. On 25 May 1946, the Emirate became the "Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan", achieving full independence on 17 June 1946 when the Treaty of London ratifications were exchanged in Amman. In 1949 the country's official name was changed to the "Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan". (See Modern Map History of Israel)

In early 1921, prior to the convening of the Cairo Conference, the Middle East Department of the Colonial Office set out the situation as follows which confirmed the Balfour Declaration:

Distinction to be drawn between Palestine and Trans-Jordan under the Mandate. His Majesty's Government are responsible under the terms of the Mandate for establishing in Palestine a national home for the Jewish people. They are also pledged by the assurances given to the Sherif of Mecca in 1915 to recognise and support the independence of the Arabs in those portions of the (Turkish) vilayet of Damascus in which they are free to act without detriment to French interests. The western boundary of the Turkish vilayet of Damascus before the war was the River Jordan. Palestine and Trans-Jordan do not, therefore, stand upon quite the same footing. At the same time, the two areas are economically interdependent, and their development must be considered as a single problem. Further, His Majesty's Government have been entrusted with the Mandate for "Palestine". If they wish to assert their claim to Trans-Jordan and to avoid raising with other Powers the legal status of that area, they can only do so by proceeding upon the assumption that Trans-Jordan forms part of the area covered by the Palestine Mandate. In default of this assumption Trans-Jordan would be left, under article 132 of the Treaty of Sèvres, to the disposal of the principal Allied Powers. Some means must be found of giving effect in Trans-Jordan to the terms of the Mandate consistently with "recognition and support of the independence of the Arabs".

The main problem after the war for Palestine was perceived beliefs. The Arabs had joined the Allies to fight the Turks during the war and convinced themselves that they were due to be given what they believed was their land once the war was over.

HOW DID THE ARAB TERRITORY OF TRANSJORDAN COME INTO BEING?

The 1922 White Paper (also called the Churchill White Paper) was the first official manifesto interpreting the Balfour Declaration. It was issued on June 3, 1922, after investigation of the 1921 disturbances. Although the White Paper stated that the Balfour Declaration could not be amended and that the Jews were in Palestine by right, it partitioned the area of the Mandate by excluding the area east of the Jordan River from Jewish settlement. That land, 76% of the original Palestine Mandate land, was renamed Transjordan and was given to the Emir Abdullah by the British.

The White Paper included the statement that the British Government:l

... does not want Palestine to become "as Jewish as England is English", rather should become "a center in which Jewish people as a whole may take, on grounds of religion and race, an interest and a pride."

(From Why was almost 80% of the Mandate territory of Palestine given to Arab Jordan?)

After the partition, Transjordan remained part of the Palestine Mandate and its legal system applied to all residents, both East and West of the Jordan River, who all carried Palestine Mandate passports. Palestine Mandate currency was the legal tender in Transjordan as well as the area West of the river. This was the consistent situation until 1946, 24 years later, when Britain completed the action by unilaterally granting Transjordan its independence. Thus the British subverted the purpose of the Palestine Mandate, partitioned Palestine and created an independent Palestine-Arab state with no regard for the rights and needs of the Jewish population. According to Sir Alec Kirkbride, the British representative in the area, Transjordan was:

... intended to serve as a reserve of land for use in the resettlement of Arabs once the National Home for the Jews in Palestine, which [Britain was] pledged to support, became an accomplished fact. There was no intention at that stage of forming the territory east of the River Jordan into an independent Arab state.

In 1925, the British added 60,000 sq. km. of desert to eastern Transjordan forming an "arm" of land to connect Transjordan with Iraq and to cut Syria off from the Arabian Peninsula. The British continued to favor exclusive Arab development east of the Jordan River by enacting restrictive regulations against the Jews, even when Arab leaders sought Jewish involvement in the development of Transjordan)

Clashing with this was the belief among all Jews that the Balfour Declaration had promised them the same piece of territory.

In August 1929, relations between the Jews and Arabs in Palestine broke down. The focal point of this discontent was Jerusalem. The primary cause of trouble was the increased influx of Jews who had emigrated to Palestine. The number of Jews in the region had doubled in ten years. The city of Jerusalem also had major religious significance for both Arabs and Jews and over 200 deaths occurred in just four days between August 23rd to the 26th).

Arab nationalism was whipped up by the Mufti of Jerusalem, Haji Amin al-Husseini. He claimed that the number of Jews threatened the very lifestyle of the Arabs in Palestine.

The violence that occurred in August 1929 did not deter Jews from going to Palestine. In 1931, 4,075 Jews emigrated to the region. In 1935, it was 61,854. The Mufti estimated that by the 1940’s there would be more Jews in Palestine than Arabs and that their power in the area would be extinguished on a simple numerical basis.

In May 1936, more violence occurred and the British had to restore law and order using the military. Thirty four soldiers were killed in the process. The violence did not stop. In fact, it became worse after November 1937.

For the Arabs there were two enemies – the Jews and the British authorities based in Palestine via their League mandate. For the Jews there were also two enemies – the Arabs and the British.

Therefore, the British were pushed into the middle of a conflict they had seemingly little control over as the two other sides involved were so driven by their own beliefs. In an effort to end the violence, the British put a quota on the number of Jews who could enter Palestine in any one year. They hoped to appease the Arabs in the region but also keep on side with the Jews by recognising that Jews could enter Palestine – but in restricted numbers. They failed on both counts.

Both the Jews and the Arabs continued to attack the British. The Arabs attacked because they believed that the British had failed to keep their word after 1918 and because they believed that the British were not keeping the quotas agreed to as they did little to stop illegal landings into Palestine made by the Jews.

The Jews attacked the British authorities in Palestine simply because of the quota which they believed was grossly unfair. The British had also imposed restrictions on the amount of land Jews could buy in Palestine.

An uneasy truce occurred during the war when hostilities seemed to cease. This truce, however, was only temporary.

Many Jews had fought for the Allies during World War Two and had developed their military skills as a result. After the war ended in 1945, these skills were used in acts of terrorism. The new Labour Government of Britain had given the Jews hope that they would be given more rights in the area. Also in the aftermath of the Holocaust in Europe, many throughout the world were sympathetic to the plight of the Jews at the expense of the Arabs in Palestine.

However, neither group got what they were looking for. The British still controlled Palestine. As a result, the Jews used terrorist tactics to push their claim for the area. Groups such as the Stern Gang and Irgun Zvai Leumi attacked the British that culminated in the destruction of the British military headquarters in Palestine – the King David Hotel. Seemingly unable to influence events in Palestine, the British looked for a way out.

In 1947, the newly formed United Nations accepted the idea to partition Palestine into a zone for the Jews (Israel) and a zone for the Arabs (Palestine). With this United Nations proposal, the British withdrew from the region on May 14th 1948. Almost immediately, Israel was attacked by Arab nations that surrounded in a war that lasted from May 1948 to January 1949. Palestinian Arabs refused to recognise Israel and it became the turn of the Israeli government itself to suffer from terrorist attacks when fedayeen (fanatics) from the Palestinian Arabs community attacked Israel. Such attacks later became more organised with the creation of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO). To the Palestinian Arabs, the area the Jews call Israel, will always be Palestine. To the Jews it is Israel. There have been very few years of peace in the region since 1948.

Instead, there was Mandatory Palestine. The idea of a mandatory nation, using the common definition of the word, is an odd one: a country that’s obligatory, something that can’t be missed without fear of consequence. But the entity known as “Mandatory Palestine” existed for more than two decades—and, despite its strange-sounding name, had geopolitical consequences that can still be felt today.

The word “mandatory,” in this case, refers not to necessity but to the fact that a mandate caused it to exist. That document, the British Mandate for Palestine, was drawn up in 1920 and came into effect on this day in 1923, Sept. 29. Issued by the League of Nations, the Mandate formalized British rule over parts of the Levant (the region that comprises countries to the east of the Mediterranean), as part of the League’s goal of administrating the region’s formerly Ottoman nations “until such time as they are able to stand alone.” The Mandate also gave Britain the responsibility for creating a Jewish national homeland in the region.

The Mandate did not itself redraw borders—following the end of World War I, the European and regional powers had divvied up the former Ottoman Empire, with Britain acquiring what were then known as Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq) and Palestine (modern day Israel, Palestine and Jordan)—nor did it by any means prompt the drive to build a Jewish state in Palestine. Zionism, the movement to create a Jewish homeland, had emerged in the late 19th century, though it wasn’t exclusively focused on a homeland in Palestine. (Uganda was one of several alternatives proposed over the years.) In 1917, years before the Mandate was issued, the British government had formalized its support for a Jewish state in a public letter from Foreign Secretary Arthur James Balfour known as the Balfour Declaration.

But by endorsing British control of the region with specific conditions, the League of Nations did help lay the groundwork for the modern Jewish state—and for the tensions between Jews and Arabs in the region that would persist for decades more. Though Israel would not exist for years to come, Jewish migrants flowed from Europe to Mandatory Palestine and formal Jewish institutions began to take shape amid a sometimes violent push to finalize the creation of a Jewish state. Meanwhile, the growing Jewish population exacerbated tensions with the Arab community and fueled conflicting Arab nationalist movements.

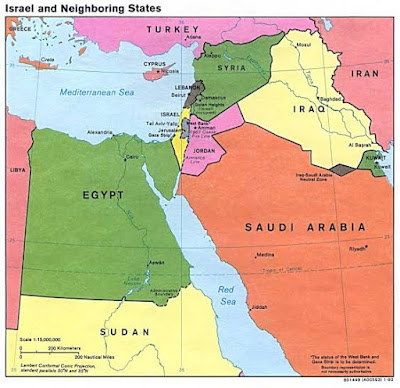

TIME reported on some of the tensions in the 1929 article from which the map above is drawn:

The fighting that began between Jews and Arabs at Jerusalem’s Wailing Wall (TIME, Aug. 26) spread last week throughout Palestine, then inflamed fierce tribesmen of the Moslem countries which face the Holy Land (see map)…

…Sporadic clashes continuing at Haifa, Hebron and in Jerusalem itself, rolled up an estimated total of 196 dead for all Palestine. A known total of 305 wounded lay in hospitals. Speeding from England in a battleship the British High Commissioner to Palestine, handsome, brusque Sir John Chancellor, landed at Haifa, hurried to Jerusalem and sought to calm the general alarm by announcing that His Majesty’s Government were rushing more troops by sea from Malta and by land from Egypt, would soon control the situation

The clashes in Mandatory Palestine, which at times targeted the British or forced British intervention, began to take a toll on U.K. support for the Mandate. As early as 1929, some newspapers were declaring “Let Us Get Out of Palestine,” as TIME reported in the article on Jewish-Arab tensions. Though the Mandate persisted through World War II, support in war-weary Britain withered further. The U.K. granted Jordan independence in 1946 and declared that it would terminate its Mandate in Palestine on May 14, 1948. It left the “Question of Palestine” to the newly formed United Nations, which drafted a Plan of Partition that was approved by the U.N. General Assembly—but rejected by most of the Arab world—on Nov. 27, 1947.

As the day of May 14 came to an end, so did Mandatory Palestine. The region was far from settled, but the Mandate did accomplish at least one of its stated goals. Mere hours earlier, a new document had been issued: the Israeli Declaration of Independence.

Comments

Post a Comment